In democratic societies

Wie wird Geschichte konstruiert und wie verhalten sich aktuell die verschiedenen Ideologien und Versionen von Gegenwart und Geschichte zueinander? Welche Rolle spielen Fakten im Verhältnis zu ihren digitalen Repräsentationen, spielt der Verlust von Bedeutung unter digitalen Bedingungen? Wie werden in Zeiten von digitaler Dominanz, Techno-Faschismus, von digitalen Echokammern, von Post-Truth und Postfaktizität, sowie des Erstarkens der extremen Rechten und des Verlusts einer gemeinsamen Wirklichkeit Erkenntnisse und Werte gebildet bzw. verhandelt? Auf welche Weise sind die Fotografie vor dem Hintergrund ihres tradierten Realitätsbezugs und Wahrheitsanspruchs und die neuen, fotografiebasierten digitalen Werkzeuge wie z.B. KI in diese gesellschaftspolitischen Entwicklungen und Aushandlungen involviert? Welche Rolle spielen sie bei der Konstruktion von Geschichte und Identität?

In democratic societies

How is history constructed, and how do the various ideologies and versions of the present and of history currently relate to one another? What role do facts play in relation to their digital representations, and what role does the loss of meaning play in digital conditions? In times of digital dominance, techno-fascism, digital echo chambers, post-truth and post-factuality, as well as the rise of the extreme right and the loss of a shared reality, how are insights and values formed and negotiated? How are photography, with its traditional connection to reality and truth claim, and new photography-based digital tools such as AI involved in these socio-political developments and negotiations? What role do they play in the construction of history and identity?

Michael Reisch, 1-2026

Work in progress: In democratic societies / „Rossebändiger“

In democratic societies / „Rossebändiger“

In meiner Arbeit In democratic societies / "Rossebändiger interessiert mich das Ringen um Deutungshoheit bzw. Wahrheit auf politisch-historischer Ebene im Verhältnis zur medialen Ebene. Das Erstarken der Neuen Rechten und das Aufkommen postfaktischer Strömungen sind direkt mit den parallel verlaufenden Diskursen zum Thema „Wahrheit“ und „Fake“ auf medialer Ebene verknüpft: Der tradierte Wahrheitsanspruch der Fotografie, ihr direkter Bezug zur physisch existenten Realität und damit ihre Glaubwürdigkeit werden durch die neuen digitalen Werkzeuge, insbesondere durch bildgenerierende Künstliche Intelligenz aktuell massiv infrage gestellt und müssen aktuell neu verhandelt werden.

Historie

Meine Arbeit In democratic societies / "Rossebändiger" basiert auf den beiden Rossebändiger-Skulpturen von Edwin Scharff (1887-1955) aus den Jahren 1937-1940, die am Eingang des heutigen Nordparks bzw. Aquazoos, Kaiserwerther Straße 390 in 40474 Düsseldorf stehen. Die Rossebändiger-Skulpturen von Edwin Scharff wurden vom NS-Regime für die Große Reichsausstellung Schaffendes Volk, der zu damaliger Zeit wichtigsten Propagandaausstellung Nazideutschlands, bei Scharff in Auftrag gegeben. Die Einordnung der Skulpturen ist jedoch historisch ambivalent: Obwohl die Arbeiten an den Skulpturen in Kenntnis der Entwürfe und Modelle, und mit Zustimmung des NS-Regimes durchgeführt wurden, wurden Fotos der Rossebändiger kurzzeitig bei der Eröffnung in der Ausstellung Entartete Kunst in München 1937 gezeigt, nach 2 Tagen allerdings mit dem Hinweis auf ein Versehen entfernt. Die Arbeiten an den Skulpturen wurden 1938 wieder aufgenommen und bis 1940 unter dem Naziregime fertiggestellt, Edwin Scharff verlor in der Folge der Ereignisse dennoch seine Anstellung als Professor an der Kunstakademie Düsseldorf.

Quellen:

- „Vom Werkbund zum Vierjahresplan. Die Ausstellung Schaffendes Volk, Düsseldorf 1937“ (ISBN 3-7700-3045-1), Dissertation, Stefanie Schäfers, Droste Verlag, 2001.

- Stadtarchiv Düsseldorf, Akte Bestand 0-1-18 Schaffendes Volk

- https://emuseum.duesseldorf.de/objects/140736/rossebaendiger, abgerufen am 15.12.2025

Statement

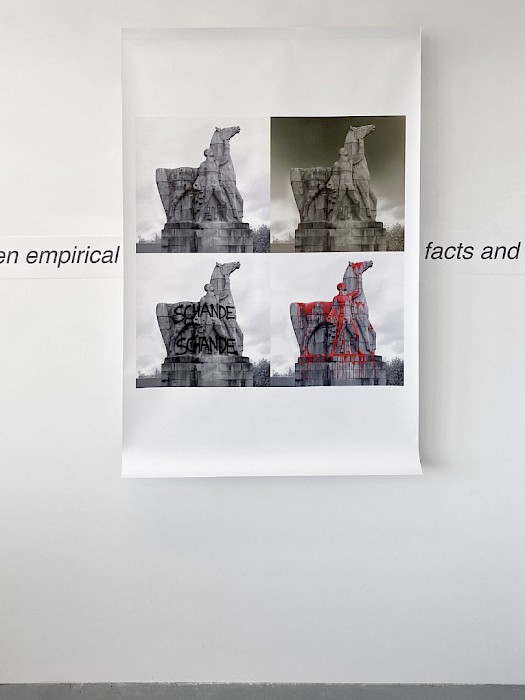

Für mich interessant ist das historische Ringen um Deutung, das sich an den beiden Rossebändigern festmacht und das ich in Bezug zur aktuellen gesellschaftspolitischen Auseinandersetzungen, vor allem hinsichtlich diverser Kulturkämpfe in Zusammenhang mit dem Erstarken der neuen Rechten setzen und auf unsere heutige gesellschaftspolitische Situation beziehen möchte: Einerseits verkörpern die Rossebändiger eine mit dem Nationalsozialismus konnotierte Ästhetik, die 12 m hohen Granit-Skulpturen waren als monumentale ideologische Wahrzeichen, als Staatskunst und Propaganda für das NS-Regime entstanden und können auf dieser Ebene auch heute noch als Symbole für den Nationalsozialismus und den Faschismus gelesen werden. Andererseits gab es bei dieser Zuschreibung durch die zeitweise Einstufung als Entartete Kunst (durch das Entfernen der Rossebändiger-Fotos nach 2 Tagen aus der Ausstellung Entartete Kunst in München und den Weiterbau und Fertigstellung der Skulpturen) einen Bruch. Eindeutige Zuschreibungen werden daher aus meiner Sicht den unterschiedlichen Bedeutungsschichten und dem Wirken der verschiedenen ideologischen Kräfte letztlich nicht gerecht. Die Rossebändiger sind in ästhetischer Hinsicht weder als reine NS-Kunst, wie beispielsweise Josef Thoraks Skulptur Fahnenträger aus dem Jahr 1937, noch als Entartete Kunst wie beispielsweise Otto Freundlichs Skulptur Der neue Mensch aus dem Jahr 1912 (zerstört 1941, auf dem Plakat zur Ausstellung Entartete Kunst in München abgebildet), kategorisierbar, so meine Einschätzung.

Ziel der Arbeit In democratic societies / "Rossebändiger“ ist es nicht, diese historischen Zusammenhänge kunstwissenschaftlich aufzuklären, meine obige Aussage ist lediglich eine weitere Meinung und reiht sich in die verschiedenen Deutungsversuche zu den Rossebändigern ein.

Vielmehr interessiert mich gerade die Unschärfe der Situation angesichts der ideologischen Gemengelage, das historische Ringen von verschiedenen Kräften um Deutungshoheit. Vor allem die Parallelen zu den heutigen Kulturkämpfen sind für mich relevant. Die historischen Rossebändiger sollen mir dabei als Projektionsfläche für unterschiedliche Bedeutungszuschreibungen und gesellschaftspolitische Intentionen in Vergangenheit und Gegenwart dienen.

Arbeitsprozess

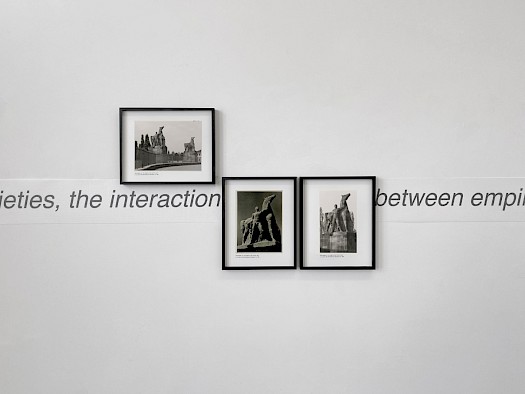

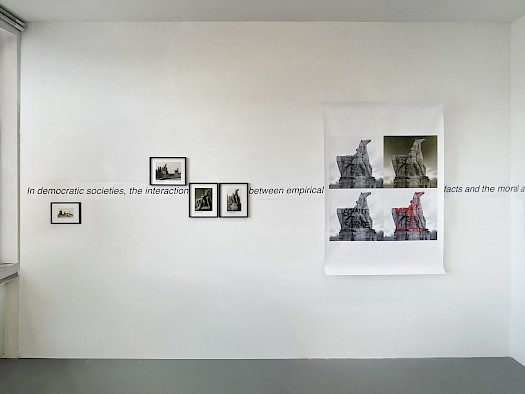

Die Arbeit In democratic societies / „Rossebändiger“ ist von mir in mehreren Schichten konzipiert, zum einen besteht sie aus dem Satz: „In democratic societies, the interaction between empirical facts and the moral and ethical frameworks through which they are interpreted plays a decisive role in shaping collective values and norms”, den ich auf Basis von akademischen, politikwissenschaftlichen Abhandlungen zum Thema Postfaktizität formuliert habe, wobei der Sprachduktus der Ausgangstexte erhalten bleiben sollte.

Zum anderen habe ich dokumentarische Fotos der Rossebändiger-Skulpturen erstellt (2014-2026), diese sind zusammen mit Reproduktionen historischer Fotos der Rossebändiger-Skulpturen aus dem Stadtarchiv Düsseldorf (aus den Jahren 1937-1960) ebenfalls Teil der Installation. Die GPS-Koordinaten und die Zeit der Aufnahme, sowie der Zeitpunkt der Erstellung der Scans der historischen Fotos im Stadtarchiv sind als Text in den Bildern sichtbar.

Diesem dokumentarisch-fotografischen Teil der Installation habe ich mit von generativer KI bearbeitete Bilder gegenübergestellt: Einige der von mir erstellten Fotos der Rossebändiger-Skulpturen sind mithilfe von generativen KI-Tools bearbeitet, hier habe ich mit Text-Prompts die bestehenden Fotos verändert, und die Skulpturen mit u.a. „Graffiti- und Farbeingriffen“ versehen. Die Graffiti-Textfragmente habe ich teils selbst erdacht, teils stammen sie aus tatsächlichen Graffiti- und Protestaktionen im öffentlichen Raum. Auch habe ich mithilfe von generativen KI-Tools Veränderungen im Erscheinungsbild der Skulpturen vorgenommen.

Alle Schichten der Installation sind durch die Materialität zu Gruppen zusammengefasst: Der Satz „In democratic societies ...“ ist auf Mesh-Plane gedruckt, der KI-Bildteil ist auf PVC-Plane gedruckt, und der dokumentarische Bildteil besteht aus Inkjet-prints in Aluminiumrahmen.

being continued

Michael Reisch, 3-2026

Work in progress: Moral_Staat_Norm

upcoming 10-2026: Projekt Kunst im öffentlichen Raum, LED-Wand: https://take-a-bow.art/

Für die Videoarbeit Moral_Staat_Norm etc. habe ich Begriffs-Felder gebildet, die aus meiner Sicht in aktuellen gesellschaftspolitischen Aushandlungen und Konflikten – u.a. Demokratie in der Auseinandersetzung mit demokratiefeindlichen Bewegungen wie Autoritarismus und der neuen Rechten; Post-Truth- und postfaktischen Strömungen, etc. – eine wichtige Rolle spielen. Ich verstehe die Visualisierung dieser Begriffs-und Konfliktfelder zum einen als kritischen Impuls; zum anderen als aktuelle politische Matrix, auf der sich neue gesellschaftspolitische Ideen und Utopien bilden können, bzw. an der sich diese Utopien beweisen müssen. (work in progress).

Work in progress: Moral_Staat_Norm

upcoming 10-2026: Project art in public space, LED-wall: https://take-a-bow.art/

For the video work Moral_State_Norm etc., I have created concept fields that, in my view, play an important role in current socio-political negotiations and conflicts—including democracy in the confrontation with anti-democratic movements such as authoritarianism and the new right; post-truth and post-factual trends, etc. I understand the visualization of these conflict fields as a critical impulse on the one hand, and as a current political matrix on the other, on which new socio-political ideas and utopias can form, or on which these utopias must prove themselves.

Michael Reisch, 1-2026